Following on from the previous ‘Provision for Pleasure’ post looking at what constituted ‘safe sex’ with regards to Georgian London’s Booming Sex Industry, time to turn to STDs.

Of course, sexually transmitted diseases have been known to mankind for centuries, but were certainly a prevalent scourge to 18th century society, especially so in the climate of London’s booming sex industry; people’s lack of awareness and understanding of STDs contributing to the widespread transmission of infections, and before the advent of modern medicine, remedies were few and hardly efficacious.

Six Stages of Mending a Face by Thomas Rowlandson, 1792, showing the various measures employed by ‘poxed’ prostitutes to disguise their condition.

From medieval times, syphilis was one of the most prevalent venereal diseases rampant throughout the sexually active population. Blame culture is nothing new, and the advent and spread of the disease in Europe was said to have arisen from the crew members who picked up the disease on the voyages led by Christopher Columbus, who if such assertions are to be believed certainly discovered more than just the New World. Supposedly spread on their return when docking at ports in Europe, syphilis, or grande verole, the ‘great pox’ as it was otherwise known went by a variety of other names, usually coined by those keen to shift the ultimate responsibility for the disease on to an enemy or a country other than their own. Consequently, the French called it the ‘Neapolitan disease’, the ‘disease of Naples’ or the ‘Spanish disease’, while the English and Italians called it the ‘French disease’ or the ‘French pox’; the Germans called it the ‘French evil’.

Whatever it was called, historians have concluded from the archives of prisons, hospitals and asylums that an estimated one-fifth of the population might have been infected at any one time, with London hospitals during the 18th century treating barely a fraction of those infected. And that treatment was mercury.

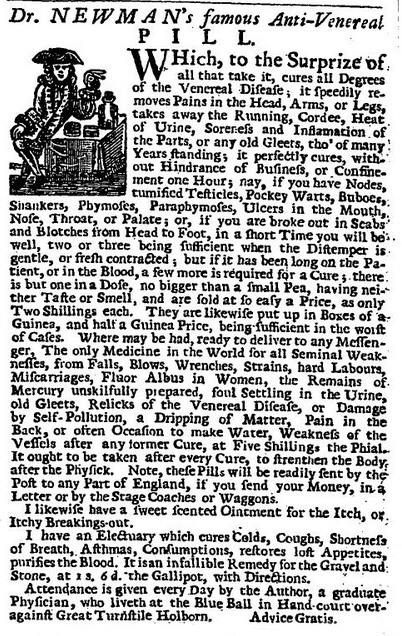

The toxicity and terrible side-effects of mercury, however, caused neuropathy, kidney failure, and severe mouth ulcers and loss of teeth, and the death of a patient often resulting from mercurial poisoning rather than from the disease itself. As treatment would often be prolonged, this gave rise to the saying, “A night with Venus, a lifetime with mercury”. There were a plethora of other spurious ‘pox’ remedies available from quack doctors, such as ‘Dr Newman’s Anti-Venereal Pills’ as advertised in 18th-century newspapers, and doubtless, these were taken by many whose gullibility lined the pockets of the likes of ‘Dr Newman’.

An advertisement appearing in The Daily Advertiser 5th August 1735 for Dr Newman’s Famous Anti-Venereal Pills.

With a view to avoiding contracting the pox in the first place, for those who could afford it, the purchase of ‘deflowering rights’ for a young virgin, as yet untainted, on the face of it seemed a costly yet worthwhile investment for a night of pleasure. (There were huge profits to be made from such sexual transactions – as much as £150 – around £11,000 in today’s money.) Yet it was not unknown for a working girl to be ‘restored’ to the financially rewarding state of virginity, some madams adept in employing various ‘secret’ procedures as a way of tricking a client into thinking he was bedding a virgo intacta.

Then there was the ‘virgin cleansing myth’, another opportunity for the bawds to profit from the belief that having sex with a virgin girl would cure a man of any sexually transmitted disease he might have contracted. Of course, the outcome was obvious: the young innocent was invariably infected herself, going on to spread the disease still further.

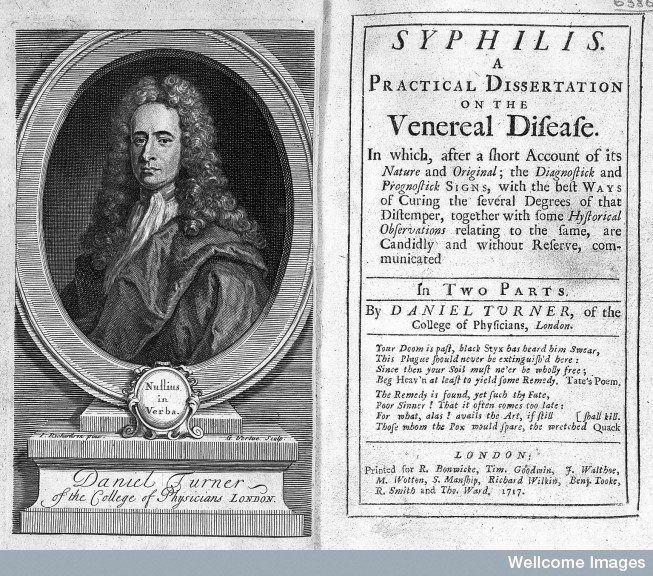

While the ‘preservatives’ or ‘assurance caps’, that is to say, condoms mentioned in the previous post were seen primarily as a means of preventing sexually transmitted diseases, rather than as an effective form of contraception, there were no guarantees; the frequent reuse of condoms, in view of their expensive nature significantly reduced their effectiveness. Indeed one English physician, Daniel Turner, stated his belief that condoms actively encouraged men to have unsafe sex with different partners, while around this time many physicians decried the use of condoms on moral grounds, the reputation of prophylactics firmly cemented, associated with philanderers, prostitutes and the immoral.

Daniel Turner’s Syphilis – A practical dissertation on the venereal disease (1717)

Then as now, the consequences of ‘indirect sexual connection’ were inescapable – the assertion that each time you sleep with someone you also sleep with their past still rings true. Thankfully today’s condoms do offer a measure of reassurance with regards to contracting an STD – so remember, ‘No balloons? No party!’