Following on from the previous ‘Provision for Pleasure’ post, time to take a look at what constituted ‘safe sex’ with regards to Georgian London’s Booming Sex Industry.

While ‘withdrawal’ was an age-old, albeit often unreliable method, interruption was hardly in the ethos of those bent on seeking pleasure and who had their heart (and their nether regions) set on a sexual encounter without the bounds of propriety. However, for those with a measure of foresight, there were contraceptive choices available in the eighteenth century, though they were often costly and there was no guarantee of reliability either. But this did nothing to diminish the thriving customer base enjoyed by ‘Mrs Phillips’ who was the proprietress of The Green Canister, in Half Moon Street (now Bedford Street) in Covent Garden. Astutely located, at the time Covent Garden – or ‘the great square of Venus’ – was the prime location for Georgian London’s sex trade, and during her time as a courtesan, Phillips had clearly learned, as well as ‘turned’ a trick or two. Handbills printed to advertise her wares were given out to prospective customers in the street by link boys, keen to earn a few extra pennies, and amongst the most popular items touted were ‘preservatives’, or, more widely speaking, condoms.

Seen primarily as a means of preventing sexually transmitted diseases, in 1776 one London advertiser described condoms as “implements of safety which secure the health of my customers”, and while there was no guarantee as to the effectiveness of 18th century condoms as a contraceptive, Casanova, best known as one of the most famous lovers in history, was one of the first reported as using ‘assurance caps’ to prevent impregnating his mistresses.

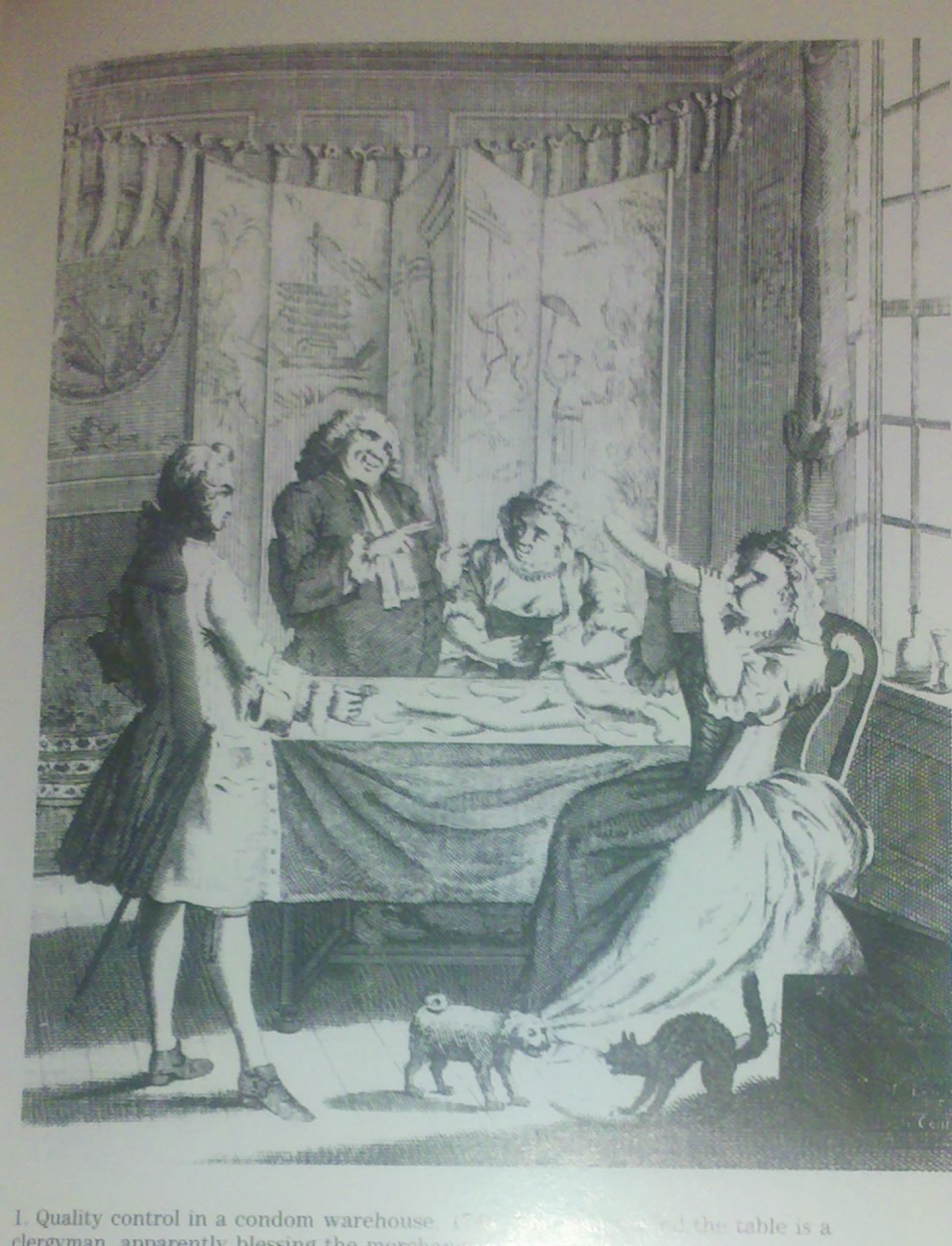

Early quality control – Casanova would often blow up a condom before use to test for holes (left) while in the caricature (right) a woman in a ‘condom warehouse’ is seen blowing up a condom to make sure that it is not damaged.

In the 18th century, condoms were available in a variety of qualities and sizes, though the standard length on offer was between seven and eight inches, secured with a coloured ribbon tied around the base. Made from either linen or ‘skin’ (sheep’s intestine) condoms could be used several times and men had only to wash them after each use. Sold at pubs, barber shops, apothecary (chemist) shops and open-air markets, condoms were also sometimes available at the theatre – it was after all the populous theatre scene in and around Covent Garden which promised a steady supply of potential sexual clients, either emerging during the intermission or seeking further entertainment after the show was over.

One firm proponent of condoms or ‘armour’ as he called them was James Boswell, whose London Journal is a richly informative source of information on sex in the eighteenth century; Boswell enthusiastically pursued a libertine lifestyle:

“At the bottom of the Haymarket I picked up a strong, jolly young damsel, and taking her under the arm I conducted her to Westminster Bridge, and then in armour complete did I engage her upon this noble edifice. The whim of doing it there with the Thames rolling below us amused me much.”

In addition to condoms, outlets such The Green Canister would also have carried variations of the contraceptive sponge, a piece of natural sponge or linen with a length of ribbon stitched to it. Soaked in a dilute solution of lemon juice, or more commonly vinegar, this was a barrier method incorporating a supposed natural spermicide and favoured by prostitutes, but also employed by ‘ordinary’ women, especially those desirous of a break from childbearing.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, women were also known to utilise half a squeezed lemon as a kind of cervical cap; mention here again of the legendary lothario Casanova who took the credit for ‘inventing’ this barrier method, though there’s significant evidence to suggest that his claim on this astringent idea was not the first. For thousands of years, women have inserted fruit acids, jellies, pastes and various objects and mixtures into their vagina in an attempt to prevent conception, with vaginal douches also used after intercourse as a contraceptive measure from at least the 1600’s.

Of course, there was one guaranteed sure-fire method of contraception universally available in the 18th century, still an option today, and one which was absolutely free – Abstinence! But then where’s the fun in that?!